The Basics Of Training For Size Or Strength

But to keep making significant progress—especially as you become more advanced—you may need to specialize your training to the point where you either train for size like a bodybuilder or strength like a powerlifter. While some programs can have elements of both, there are important distinctions in how each kind of athlete trains.

Even an onlooker with an untrained eye can notice the difference in the training methods of powerlifters and bodybuilders. While they share the common ground of barbells and dumbbells, the utilization of these implements is often drastically different.

What are those differences, why do they exist, and how do you optimize your training to gain either size or strength? There’s been plenty of research on just those topics, so let’s take a closer look.

The Adaptation Process

Your body has a single, uniform purpose: to survive. To do that, it communicates with your environment via adaptation. The environment starts the conversation by imposing stress on your body, and your body responds by selectively adapting in a way that best suits its survival chances.

Front Barbell Squat

Training, then, is a conscious communication with your body—imposing self-selected stress to mold your frame into a desired shape, or increasing your capabilities beyond their current state. It’s a powerful farce. You convince your body that, if it doesn’t meet your demands, it will perish. This, of course, isn’t true, but it’s the true power of training.

Let these ideas frame your thought process as you examine the rest of this article. Growing or getting stronger is the outcome of effective physical communication. Be sure you’re telling your body exactly the things you want it to hear!

Size And Strength: The Difference

Let’s start by stripping the difference between size and strength training down to the barest essential.

The simplest difference between building size and boosting strength is training volume. Hypertrophy requires more total training volume than strength-building does.

Training volume is the number of sets and reps you do in a given workout. The more exercises you do for a body part, and the more sets you do of a given exercise, the greater your training volume.

Of course, there are other variables that impact how your body will adapt to the training stress you impose on it.

Let’s take a closer look at each goal.

Goal 1. Building Muscle Size (Hypertrophy)

So, what makes muscles bigger? Stress—another way to refer to the amount of weight you lift—is the primary answer. But you want the degree of stress that tells your body, “Get bigger or you’re kaput, my friend.”

You already know that hypertrophy requires more total training volume than building absolute strength, but that doesn’t mean you get to eliminate load (weight) from the discussion. You’re still going to use the heaviest weight possible, but the need for more training volume—your body needs reps, too—dictates that the weights are lighter than those used for building absolute strength. Blending the right amount of volume with the right amount of load creates stress that translates into growth.

Face Pull

When performing your main lifts—full range-of-motion barbell bench presses, squats, deadlifts, and rowing variations—do 20-36 total reps (all reps of all working sets of that move) with a load around 70-85 percent of your one-rep max (1RM). For example, if your max bench press is 255 pounds, use a weight that’s about 180-215 pounds.

There are a variety of volume breakdowns—4 sets of 5, 4 sets of 6, 5 sets of 5, and 6 sets of 6— commonly prescribed. Progressing from 4 sets of 5 with heavier loads to 6 sets of 6 with slightly lighter loads is a simple and effective strategy.

Rest between sets is also an important consideration. With hypertrophy training, there’s an accumulation of stress that coerces muscle cell growth. There’s a rest-time sweet spot that accumulates stress while allowing enough recovery to keep loads in your desired percentage range (70-85). That sweet spot hovers around the two-minute mark, depending on the lifter’s condition and experience.

Assistance exercises, or the exercises that follow your heavy barbell lifts, should be done with more volume and shorter rest periods. Here, the total number of reps per exercise should fall between 30 and 50. Rest periods range from nonexistent to 90 seconds, depending on the load and set-and-rep scheme.

Doing 3-5 sets of 10 with 60-90 seconds rest is common in first-level assistance exercises in hypertrophy programs. Nothing fancy here, but it gets the job done.

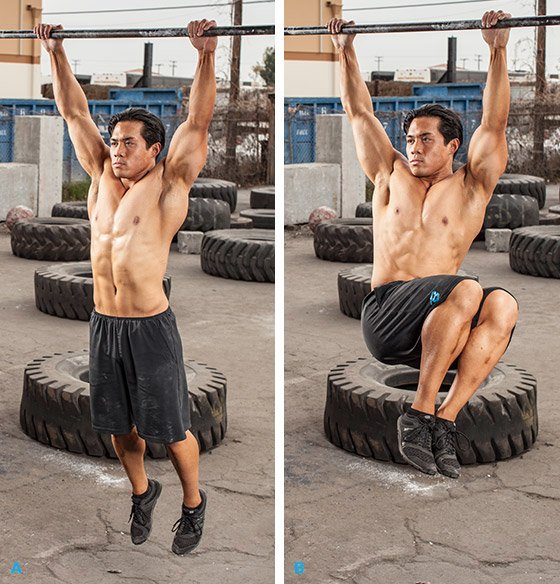

Hanging Leg Raise

On assistance exercises, choose exercises that improve upon your weaknesses—aesthetic or otherwise. For example, if the flat bench press was your main lift, the incline or decline bench press is a solid choice for your first assistance exercise. Dumbbell variations also work as assistance exercises, but it’s best to use them after completing a few barbell lifts. You want to accumulate a lot of barbell stress before employing less stressful dumbbell work.

Program structure usually depends on the individual, but typically it’s 3-5 multijoint assistance lifts following the main heavier barbell exercise.

Goal 2. Building Strength

To build absolute strength, the stress communication changes in a few ways. For one, as stated earlier, you’ll use less training volume. You’ll also include heavier weight and fewer reps per set.

Strength programs are structured similarly to hypertrophy programs—a main lift followed by assistance lifts—but here you’re drastically cutting the number of reps per set because you’re significantly increasing the weight.

Main lifts fall in a percentage range of between 80-90 percent of your 1RM. The total number of reps for main lifts also drops to 10-20 total. At certain times, however, strength programs increase load above 90 percent of your 1RM; at those times, the total reps are significantly cut further. Here, no more than 10 are completed during a training session.

To accumulate the total volume, you’ll use sets of 2-4 reps in the range of 80-90 percent of 1RM. If you climb above 90 percent, cut the reps per set to 1-2.

Rest periods between sets are an eternity compared to those of a hypertrophy program, but they’re necessary since heavier loads are more neurologically demanding than lighter ones. The nervous system requires considerably more rest than does muscle tissue. Rest 3-5 minutes between sets of the day’s main lift.

Incline Dumbbell Press

Assistance training for absolute strength is much different than what’s programmed for hypertrophy. Most new lifters botch this process and overload their nervous system. Commonly, beginners treat absolute strength assistance as if it were hypertrophy assistance—lots of sets, lots of volume. That dog just won’t hunt. Attempting to maintain the same volume while increasing intensity is a plan destined to fail.

Absolute strength assistance training exists in the 15-25 total rep range, with loads between 70-80 percent of your 1RM. You’ll also use fewer total assistance exercises, roughly 2-4 instead of 3-5. Without this reduction, it’s difficult to recover, and overtraining eventually becomes reality because you’ve giving your body more stress than it can accommodate.

In this assistance-training realm, exercises are chosen specifically to abolish weak points in your main lifts. Let’s demonstrate with the deadlift. Say you have a hard time breaking the plates from the floor, but once you get the bar moving, you finish the lift without difficulty. After your main deadlifting sets, your first assistance exercise should be one that attacks your weak point. Snatch-grip deadlifts and deficit deadlifts are two great options.

Choose the rest of your assistance exercises in much the same way, ensuring that you build a complete, strong main lift. Check out this example strength routine.

Start With Strength

These points are meant as general guidelines to get you started. Reality, of course, is situational—it all depends on your starting point.

If you’re a newbie, any program is a strength and size program. Simply stressing your frame via any load and volume combination is enough to build muscle and develop force. The same is often true for those who have been on gym hiatus.

Hypertrophy and strength training begin to dovetail only when a trainee has accomplished a reputable degree of strength. It’s at this point that your stress communication must specifically dictate the desired adaptation.

Hypertrophy now requires different stress and more volume than it did as you trained yourself from beginner to intermediate. For best results, follow the principles discussed earlier in this article.

I like to start by setting—and accomplishing—respectable strength goals. Do this, and it’s easier for you to amass your ultimate hypertrophy goals.